THEME: Mediation and International Politics

This article was authored by Aniket Chauhaan and Suhani Agarwal from NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad.

Abstract

In this essay, we will be focussing on the sociological aspects of the mediation proceedings along with the legal one. This piece talks about why mediation is an essential, albeit unexplored option under the present jurisprudence when trying to resolve the religious conflicts, more so because of the vast number of difficulties that it faces. Religious conflict, itself, as we explore here, has a broad ambit that is not restricted to large, headline catching and violent religious spars but includes other, smaller cases wherein mediation will serve as a more effective dispute resolution mechanism.

Scope of the Essay

Through this essay, we will predominantly try to explore the viability of mediations in cases of religious conflict. We delve into power imbalance that exist in a religious conflict and how that impedes proper mediation proceedings. Moreover, we see the application of mediations to not just substantive conflicts but also to the more ‘trivial’ or individualistic one along with a sectarian conflict called intra-religious conflicts. To close, we also give certain guidelines that can be followed to make mediation a more mainstream way of tackling with religious conflicts.

Reason for Selecting this Theme

In the current political scenario- not only nationally but globally as well, religion plays a very significant role. Today the world stands in the middle of violence and destruction caused because of conflicts of faith. The political and legal system is being swayed away by such religious sentiments. In such conditions, it becomes imperative to look at the broader picture and explore all possible alternatives through which such conflicts could be resolved efficiently.

The reason for choosing this theme was to explore mediation as one of such alternate avenues. Through mediation, people can learn to become more tolerant and respectful towards the values and belief of the opposite party, in essence, sensitizing them to the other’s perspective and faith. The authors aim to show how plausible this alternate method is in resolving inter-religious and intra-religious disputes.

Domestic and Global Contextualisation

This essay is India centric as will be evident from the examples and laws talked about, however, we feel that what is seen in India is also applicable, to some degree, to other parts of the world. Mediation’s use and importance has been recognised world over. All major countries have some laws or frameworks that deal with alternate dispute resolutions in general and mediation in particular. Even the International Court of Justice has provisions for mediations however, the ICJ has never dealt with a religious conflict, because the vast majority of issues related to religious freedom arise in the context of disputes between factions within a state’s borders and therefore and hence, fall outside the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[1]

Religious conflicts are nothing new to the foreign nations as well, the largest conflict fuelled because of religion is the Israeli-Arab conflict which has seen a lit of mediation proceedings among the states, sometimes successfully however, most of the times in vain. In state-based conflicts, however, the same tenets will generally apply, as the ones we have talked below as it is a global trend of religious conflicts getting smudged with ethnic, social and political colours and motives.[2] Religion maybe as sensitive a topic as it is in India or it may not but the conflicts may still have multiple stakeholders and other characteristics mentioned hereunder, around the globe. Hereunder, are some instances where religious disputes are resolved through mediation.

In Nigeria, mediation organizations have emerged to reduce instances of religious violence. Such an example is Interfaith Mediation Centre established by Imam Muhammed Ashafa.[3] The organization has facilitated compromises among religious leader, such as the Kaduna (or Kafunchan) Peace Declaration.[4] However, in the North-Eastern part of the country where there are still violent attacks by Boko Haram, there has not been much development, stemming from the fact that it is difficult to get one of the parties to a mediation table.[5]

‘Tradition and Faith Oriented Insider Mediators’ or TFIM, use religious beliefs to facilitate dispute resolution by faith-based explanations and by drawing motivations from certain religious and non-religious aspects. They operate around the globe and are a network of individuals that undertake such tasks. They have resolved disputes in smaller and turmoil plagued countries, like Mali, Lebanon, Kenya, Thailand, Columbia and so on.[6]

Introduction

“The Chief Ministers and Chief Justices were of the opinion that Courts were not in a position to bear the entire burden of justice system and that a number of disputes lent themselves to resolution by alternative modes such as arbitration, mediation and negotiation. They emphasized the desirability of disputants taking advantage of alternative dispute resolution which provided procedural flexibility, saved valuable time and money and avoided the stress of a conventional trial.”

- Resolution adopted by the Chief Ministers and the Chief Justices of States in New Delhi on 4th December, 1993 under the Chairmanship of the then Prime Minister of India and presided over by the Chief Justice of India.[7]

The above-mentioned paragraph captures the essence of the merits and importance of the mediation proceedings. Mediation finds mention under article 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure along with the Order X of the same act that mentions the procedural aspect of how mediation will apply in cases. And even though mediation has carved for itself a place in the present legal system, owing to its wide application in divorce proceedings, the same cannot be said for its application to resolve religious conflicts, despite the fact that the Supreme Court has declared it to be mandatorily by the courts if they find that there are grounds for compromise[8], something which even they have failed in complying with.

Blake and Mouten’s two-dimensional grid, to study conflicting styles, developed five styles that people tend to adopt when faced with a conflict[9]:

- Dominating or competing

- Integrating

- Compromising

- Avoiding, and

- Obliging

Mediation, as an activity, operates when both the parties jointly follow the third style that is, of compromising. However, the nature of religious conflicts, especially the ones that are sensationalised, becomes that of the first style- trying to dominate over the other. The fundamental difficulty faced with mediation in this context, as a form of dispute resolution, is commuting the nature of the religious conflict from a dominating to a compromising style.

Evidences of Mediation in Religious Texts

Peaceful dispute resolution by means of effective communication is not new for religions, many religious texts and epics have historically talked about the process. Through a fair mode of dialogue and discussion, conflicts could be resolved in an amicable, faster and cheaper way, something that sacred texts have recognised. All major religions of the world like Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism instruct methods very similar to modern alternate dispute resolution mechanisms to resolve dispute rather than through arms and ammunitions.[10]

Islam recognizes processes of mediation (Wasaatah) and conciliation (Sulh). The chapter four of the Holy Quran, mentions amicable way of finding solutions to disputes-

“In most of their Secret talks there is no good; but if one exhorts to a deed of charity or justice or conciliation between men, (secrecy is permissible): to him who does this, seeking the pleasure of Allah, we shall soon give the reward of the highest (value).” [11]

Not only this but there it also reiterates the importance of fair and just mediation process, without any biases.

Christianity too implicitly talks about need of mediation.[12] It says that a person should solve the dispute outside the court itself, this is clearly demonstrated in this paragraph-

“If your brother sins against you, go and show him his fault, just between the two of you. If he listens to you, you have won your brother over. But if he will not listen, take one or two others along, so that every matter may be established by the testimony of two or three witnesses. If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if he refuses to listen even to the church, treat him as you would a pagan or a tax collector.”[13]

As per the Gospel of Luke “When you are on the way to court with your accuser, try to settle the matter before you get there. Otherwise, your accuser may drag you before the judge, who will hand you over to an officer, who will throw you into prison.”[14]

Moreover, famous Hindu epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata have given significance to dialogue and negotiation. Before attacking the fortress of Lanka, Lord Ram sent Angad, a loyal commander of his army to talk to Ravana so that the matter could be resolved instead of going to war which will lead to death and destruction.[15] A similar stance was taken by the Pandavas in the epic of Mahabharata, when they asked Lord Krishna to mediate between the them and the Kauravas. Lord Krishna was chosen because of the neutral position he held amongst the kuru lineage. It was only when Kauravas refused to accept any middle ground, that the one of the biggest wars of all time broke out, which soaked the history of the “Kuru Vansh” with bloodstains.[16] Both Ravana and the Kauravas could have agreed to avail the peaceful means of negotiation instead they let their pride consume their intelligence leading to mass destruction.

Violence is considered to be the last resort in most of the mainstream religions, after every possible way of mediation and conciliation has been exhausted. Mediation is also given precedence over formal justice mechanisms. This is because when parties agree to mediation, it shows their willingness to comply and to be flexible enough to accommodate view points on both sides. However, herein lies the paradox. Even though religions preach the importance of compromise and mediation, a religious conflict rarely reaches the table of a mediator while the more extremist side of the religion gets more attention.

Need for Mediation in Religious Conflicts

The Indian judiciary, like most common law countries, follows an adversarial system.[17] An unbiased judge presides over a case and it is up to either of the sparring litigants to prove their case before the judge who plays only a passive role and does not involve himself or herself into the investigations of the case. However, that becomes problematic for a country like ours when there are religious conflicts.

Religion, in India, is not only an individualistic experience. It encompasses a large part of the social life of the people in the country. The citizens are heavily invested in their religion and religious life. Moreover, religion, in a large number of circumstances, because of its overt and extrinsic involvement in people’s lives, gets entangled with the social and political issues, often, even giving rise to them. A lot of times, in fact, issues that do not have anything to do with religion are also interpreted on religious lines.[18]

There is a dual nature of religion that is seen in India: The constitution has to a limited extent, inculcated a value of tolerance, among a large number of people in the country along with a culture of discussion. However, religion is an extremely sensitive subject in a number of cases, stemming from the earlier mentioned point of it getting entangled with social and political issues and it is the second nature that has largely been on the forefront because of its controversial and sensational character. However, at the same time, there is an undercurrent of the first one that does not get enough coverage, and even though on the backseat, does exist in society.[19] Mediation could provide a way to the parties to engage and seek clarification, not only on the issues of faith but also on the stance of the opposing party which could essentially increase the chance of finding a common ground.

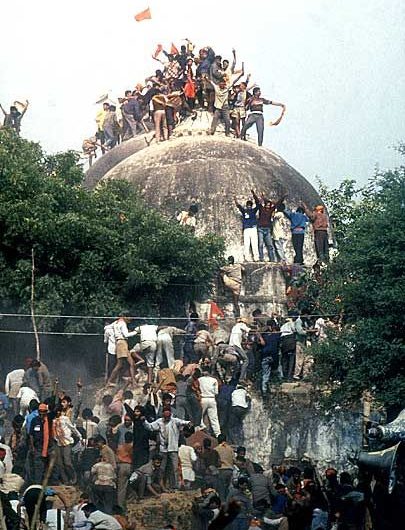

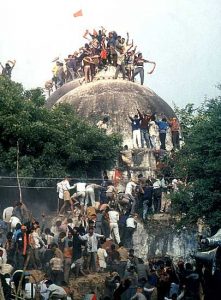

In these circumstances, the litigation proceedings lead to an overt conflict after which, people either construe one or the other party as “winners” or “losers” which goes against a harmonious system of dispensing justice. Mediation, in these circumstances can help the society, as a whole, to get out of this conundrum. Mediation proceedings, in its basic essence, are a compromise and a good compromise can help solve the earlier stated issue, something which will only further the tolerance in the society, especially in the high profile and sensitive nature of cases like the Ayodhya dispute where the mediation proceedings, even though instituted by the Supreme Court, failed.[20] The religious parties to the case are enabled to approach a mediation centre or a mediator at their own volition, without any court interference in what is referred to as ‘pre-litigation mediation’ to resolve the dispute. If both parties are equally ready to reach a compromise, only then this method is viable for the disputes.

Pitfalls of Religious Mediation in Substantial and Far-Reaching Conflicts

Religious conflicts have also led to violence in the past. However, in these instances, especially the ones that happen on a large scale- riots or religious cleansing, mediation seems like a depraved and unconscionable way of resolving dispute. Especially, when one faction is much more powerful and dominant than the other. It seems morally reprehensible to mediate between a group that imposes their dominance upon others and a weaker, more vulnerable group. Say, for example, even the hypothetical thought of perpetrators and victims of the Kashmiri Pandit exodus, Bombay riots or the Godhra riots sitting on a table and “compromising” is deeply unsettling. Moreover, in all practicality, a fair mediation can only happen amongst equals.[21] In these cases, litigation is seen as a fairer way because in that is decided on the merits, rather than the whims of the parties, or any one of them.

These fears of mediation proceedings are true. Mediation, being a non-binding procedure falls in a trap which makes the mechanism the prerogative of the parties and in a case like above, where there exists a dominant and a weak party, the dominant party has no incentive to settle, willingly that too, for any unfavourable compromise and would not hesitate to walk away from the mediation proceedings. This poses a very large question when talking about the realizability of mediation as an established way of solving religious mediation.

Another major problem with mediating in a religious conflict is that there is no single representation of the religious stakeholders. The Ayodhya dispute had multiple parties[22] which is a characteristic of such complex and historical disputes. Every party brings different demands to the table and makes the whole process of the mediation more complex, although not impossible. However, this multi-party mediation has more chances of failure due to dissatisfaction of any single party. The religious organizations and even common people invested in the religious life will, in almost every circumstance, question anything that is achieved out of court, for lack of legitimacy[23] in their minds.

Furthermore, the mediation proceedings are meant to be confidential.[24] However, any “closed door” negotiation will have less legitimacy in the eyes of the general population, who, in this case, can be considered to be stakeholders in large religious disputes. Moreover, sometimes in these cases, more than the organisations (that are party to the case) themselves, the parties represent a section of the population, in a representative way. Hence, the people should know everything about the proceedings in such cases, especially that concern the whole religious community for it to be able to allow some acceptance and compliance.

Widening the Understanding of the phrase ‘Religious Conflicts’

A religious conflict, however, is not just limited to the large issues that form controversial headlines. A religious conflict’s definition and understanding should be broader than that. Hereunder, we delve into two of such aspects, to move away from the old and narrow understanding of a religious dispute to a more unconfined space and meaning that can truly capture more aspects of it.

1. Smaller, Inter-Religious Conflicts:

As much as religion is about the community, it is also an extremely personal affair. Every person has their own way of interpretation of religious doctrines. The environment a person lives in, their family, upbringing, education and experience shapes how they perceive religion. Since there exists such diverse faith, disputes are inevitable. Religious conflict is a broad term encompassing in its ambit not only major communal issues that could potentially lead to violence or could hurt the sentiments of an entire community, but also personal bilateral issues.

These include certain trivial activities of everyday life (when seen from the wider societal perspective), like a company refusing a job to a qualified woman wearing headscarf to work in a factory because of safety concerns or dress code. Wearing a headscarf is sacred for that woman and safety and security of its workers is the prime duty of the company. The issue has a possible chance to be mediated where both the parties come to a common ground and acknowledge that both of them are justified at their end. They could come up with a plausible solution where both could compromise and accommodate. The pitfall of mediation of pivotal issues is having multiple stakeholders in most instances, and that does not apply in such minor religious conflicts because they are of a bilateral nature.

These instances are different from the above mentioned, more substantive issues though and these call for confidentiality, as discussed in the Moti Ram v. Ashok Kumar case cited above because confidentiality becomes a major advantage for the parties as there is a high likelihood that the parties may want to keep these personal issues off the public domain.[25] Confidentiality gives a right to the parties to protect their private information that might have a bearing upon their future possibilities. This increases confidence of the parties in the process and gives them an incentive to opt for mediation.

The binding nature of litigation is a major reason why parties should for alternate dispute redressal mechanisms. Any judgement given by the court will be binding on the parties even when the parties may not agree to the proposed solution. Formal litigation not only takes a lot of time but also resources. For bilateral issues, with parties holding much smaller resource pool, mediation seems to be comparatively cheaper and hence, more viable.

2. Intra-Faith Conflicts:

Religious disputes include not only inter-faith mediation but also intra-faith mediation. Religion itself is divided in many sects and sub-sects which lead to conflict within the religion. Conflict say between the Catholics and the Protestants or sub-sects in Hinduism have a chance to be resolved through mediation. The major religions are dendritic in nature. They have different schools of thought and different belief systems within the religion. This provides for diversity and predictably, conflicts within that religion as well, called intra-religious conflicts.[26] Mediation is a viable way to solve disputes between or among these parties, especially in the cases where the sects are smaller and so is the size of conflicts.

Intra-faith conflicts are a mix of characteristics of both, the more substantive issues talked about earlier and the smaller, bilateral issues talked above. In that, it is not strictly bilateral and may have multiple stakeholders however, at the same time, it is also not as huge in proportions as the sensitive and pivotal issues talked about earlier.

It is also easier to agree of certain fundamental religious issues in these mediations because of which compromise, at least in a few cases, would be quicker and less problematic. At the same time though, the problems of the sensationalised religious conflicts also apply in this case, in a more limited fashion. All considered however, just getting all parties to come to a common forum to engage in dialogue would also be helpful because even that is missing today. For instance, the Shias and the Sunnis who are regularly under conflict do not have a lot of dialogue between them.[27]

Suggestions for Improvement

There are two prominent types of mediation process- evaluative and facilitative.[28] As the name suggests evaluative mediation is when the mediator takes up a more active role and evaluates the legal aspect of the issue. Here the mediator himself gives recommendation to the parties also explaining the possible outcomes of litigation. It does not focus much on the communicative aspect. In this type of mediation, the mediators are generally legal experts as they must know about the legal areas regarding the issue to assess the outcome. This could create a dilemma in interfaith mediation as there is a probability that the person might not be sensitive enough to the religious problems.

On the other hand, in facilitative mediation the mediator takes a more passive role. The main aim of this kind of mediation is to facilitate conversation so the parties could mutually come to an agreement after understanding the views of the opposing party. The mediator makes no recommendations and does not provides his/her opinion. This is a more plausible option for inter-faith dispute because of its communicative nature and that is what should be followed in these circumstances.

Professor Leonard Riskin also provided a mediation grid model where he talked about narrow and broad mediation types.[29] In the narrow mediation the mediator focuses on a specific legal issue of the process while in broad mediation the mediator highlights the underlying concerns of the opposing parties deeply involving with the demands of the parties. The best way possible to mediate interfaith issue is to adopt a facilitative broad mediation approach, which will help the parties to come up with their own solution. It has a better chance of being accepted since the parties themselves came up with the solution, something that should be followed in the case of these religious mediations.

Moreover, in 2016, there were certain mediation guidelines that were released by the government that were supposed to be followed in commercial mediations. Even though the Supreme Court has constituted a new committee to draft guidelines for mediation[30], a more proprietary system is important in religious disputes. For if religious mediation needs to become a more mainstream and viable dispute resolution mechanism, the procedure should be altered slightly to suit the needs of these conflicts for there are more ethno-political determinants in these instances.

Furthermore, it should be ensured that the believes of any religion per se, are not questioned rather, they just discuss the applied implications of their practices and “the aim is to find and implement joint practical solutions to the parties of the conflict.”[31]

Lastly, we can make religious leaders aware of the merits of a mediation proceedings and incentivize them to use this mechanism when faced with a religious dispute and also suggest them to other followers who are faced with such a situation where mediation would be a healthy alternative to litigation, especially since certain religious leaders have a lot of persuasive power and authority in these matters and they might appeal to a different side of an individual to persuade him or her to choose mediation, especially given the fact that such a compromise driven mechanism is talked about and also endorsed in most religious texts, as mentioned above.

Conclusion

The landmark Keshavananda Bharti[32] judgement gave a broad framework of the essence of the Constitution and formed a “basic structure”.[33] Preamble was held to be the basic structure of the constitution in the case of S.R. Bommai vs Union of India.[34]Amongst the many core values we adopted, one of them is also of fraternity.[35] It means a sense of brotherhood among the people of India. The constitution makers envisaged an India where everybody lived with harmony and tried to cultivate a sense moral responsibility to not adopt violence. Not only this, the fundamental duties under the Constitution[36] also promote brotherhood and harmony. Mediation is way through which people could understand and make compromises with the other side rather than making the issue about winning or losing.

Most of the religions also support and promote mediation as a way to resolve dispute. As the principles of non-violence or “Ahinsa”[37] are upheld by all religions, mechanisms similar to mediation were seen as the way forward. If mediation is to be used in religious matters that are of public interest, there is a high probability that such mediation does not lead to any positive outcome. With a large number of stakeholders, getting everybody on the same page is a near impossible task. But mediation is a viable option to solve smaller bilateral issues and may also be extremely helpful in intra-religious conflicts. The advantages of mediation like confidentiality and non-binding nature of the solution could be very significant to resolve these issues.

With communicative ways and adoption of what Riskin terms as facilitative broad mediation approach[38], mediation could be better utilized to understand the other party and their sentiments, which could result in a possible compromise. In current times, Alternative Dispute Resolution methods are gaining acceptance in the society. Judiciary in our country is over burdened with a huge backlog of pending cases, in such situations, methods like mediation and conciliation could reduce this burden. A very important component of this process is the willingness of the parties to commit to these procedures, keeping their shared interests in mind. The religious groups in modern times need to shed the ingrained ultra-conservatism, and accept the need to resolve disputes in a more peaceful manner.

[1] Anagha Sundararajan, Religious Freedom and International Law: The Protection of Religious Minorities in International Tribunals, INTERNATIONAL IMMERSION PROGRAM PAPERS, University of Chicago, 2017.

[2] Christopher Callaway, Religion and Politics, INTERNET ENCYCLOPEDIA OF PHILOSOPHY.

[3] Olusola O. Isola, Inter-Faith Conflict Mediation Mechanisms and Peacebuilding in Nigeria, Presented at INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND PEACEBUILDING, 2014.

[4] Kafunchan Peace Declaration, 23rd March, 2019.

[5] Supra note 3.

[6] Mir Mubashir and Luxshi Vimalarajah, Tradition & Faith Oriented Insider Mediators in Conflict Transformation, THE NETWORK FOR RELIGIOUS AND TRADITIONAL PEACEMAKERS, 2016.

[7] Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

[8] Salem Advocate Bar Association, Tamil Nadu v. Union of India, (2003) 1 SCC 49.

[9] Blake, R.R. and Mouton, J.S., The Managerial Grid, GULF PUBLISHING, Houston, 1964.

[11] An- Nisaa:114, The Holy Quran.

[12] Mathew 18:15-17.

[13] Id.

[14] Luke 6: 27-30.

[15] Narayan, R. K. Kampar, The Ramayana: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of The Indian Epic, New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

[16] N.V.R. Krishnamacharya, The Mahabharata, Tirupati: Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, 1983.

[17] Vijay, Yash S., The Adversarial System in India: Assessing Challenges and Alternatives, SSRN, Sept, 2012.

[18] Wilson, J.S. (1992), Turmoil in Assam, STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 251-66.

[19] Manju Shubhash, Rights of Religious Minorities in India, National Book Organization, New Delhi, 1988, p. 141.

[20] Shruti Mahajan, Ayodhya Dispute: From 2010 to 2019, the journey of the case in the Supreme Court, BAR&BENCH, Nov 9, 2019.

[21] Ali Khaled Qtaishat, Power Imbalances in Mediation, ASIAN SOCIAL SCIENCE; Vol. 14, No. 2, 2018.

[22] M. Siddiq v. Mahant Suresh Das, 2019 SCC OnLine SC 1440.

[23] Thota Narasimha Rao, India-Pakistan Relations: Issues, Problems and Recent Developments, ACADEMIA.EDU, http://www.academia.edu/30366858/India-Pakistan Relations Issues Problems.

[24] Moti Ram(D) Tr.Lrs.& Anr vs Ashok Kumar & Anr, (2011) 1 SCC 466.

[25] Id.

[26] Linda M. Woolf and Michael R. Hulsizer, Intra- and Inter-Religious Hate and Violence: A Psychosocial Model, JOURNAL OF HATE STUDIES, Vol. 2:1, Webster University.

[27] Dino Krause, Isak Svensson and Göran Larsson, Why Is There So Little Shia–Sunni Dialogue? Understanding the Deficit of Intra-Muslim Dialogue and Interreligious Peacemaking, RELIGIONS, 4th Oct, 2019.

[28] Douglas Noll, A Theory of Mediation, Dispute Resolution Journal, Feb. 2001.

[29] Leonard L. Riskin, Decision Making in Mediation: The New Old Grid and the New New Grid System, NOTRE DAME LAW REVIEW, Vol. 79:1, 12th Jan, 2003.

[30] Ajmer Singh, Supreme Court forms committee to draft mediation law, will send to government, ET, Jan 19, 2020, 11.40 PM IST.

[31] Jonas Baumann, Daniel Finnbogason & Isak Svensson, Rethinking Mediation: Resolving Religious Conflicts, POLICY PERSPECTIVE, Vol. 6/1, ETH Zurich, Feb 2018.

[32] Kesavananda Bharti v. State of Kerela, (1973) 4 SCC 225.

[33] Id.

[34] S.R. Bommai vs Union of India, (1994) 2 SCR 644.

[35] INDIAN CONST., Preamble.

[36] INDIAN Consti., Art. 51A(e).

[37] Walli, Koshelya: The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought, Varanasi 1974, p. 113–145.

[38] Supra note 29.