THEME: Mediation and International Politics

This article was authored by Saumya Jain and Lakshya Gupta from JGLS, O.P Jindal Global University

Abstract

Mediation is a method of alternate dispute resolution, where a third-party acts as a neutral facilitator to help reach a speedy conclusion in a conflict. Over the last decade Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) Mechanisms, including mediation, have become a focal point of discussion on the domestic as well as the international plane. In this essay, we aim to investigate first what constitutes a ‘religious’ dispute under law and then to check whether such disputes can possibly be mediated upon. Part I of the essay looks at the current position in India regarding mediation in religious disputes. The broad parameters of ‘religion’ as defined by Courts, as well as various legislations enacted in the furtherance of resolution of religious disputes are discussed. This is followed by a brief discussion on the problems faced in mediating such disputes in the country. Part II looks at similar provisions in different countries and attempts to compare and contrast the position in India. It also discusses the application of mediation as a tool in the larger context of international conflict where States and not individuals or communities are involved as actors. To do this we delve into the historical basis for adopting a conciliatory rather than an adversarial approach and map down the trajectory to present day resolution of conflicts. It also discusses the possible pros and cons of using a conciliatory approach on such a grand scale. Finally, we present our conclusion on whether mediating religious disputes is feasible or not, both domestically and as part of resolving both national and international conflict.

Introduction

Religion is a loaded term, which can hold varying connotations and instil different feelings in diverse individuals. It can signify both the collective and the individual. As a collective, it focuses on the community-forming aspects of religion by looking at group-dynamics and emphasizing cultural identity. Conflict can arise when religion becomes an identity-marker and then used to look at other communities as ‘other’ or ‘different’ from your own. During such turmoil one usually turn towards the law for guidance. However, jurisprudence both on the domestic and international front is limited when it comes to religion.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes the right of all individuals to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.[1] Even though it is not given as much importance under international law as other political conflicts, the right to free expression of one’s religion finds reference in the Genocide Convention[2] and the Refugee Convention.[3] The 1970 UNESCO Convention also makes a reference to religion by providing for the protection of religious property by protection of cultural heritage.[4] However, since religious disputes largely arise amongst groups within the same country, and rarely take on inter-country dimensions, they haven’t been the subject of adjudication on the international level very frequently. The Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) has nevertheless emphasized the duty cast on countries to give equal treatment to their minority communities in the few cases where it has adjudicated upon minority rights.[5] But it has found itself powerless to successfully adjudicate an armed religious conflict.[6] Thus, existing conflict resolution and prevention methods are not entirely capable of resolving such disputes.

Mediation is an emerging form of dispute resolution mechanism in India and worldwide, which has also gained prominence in peace negotiations in conflicts with a religious motive. Apart from United Nations (UN) sponsored mediations, there have been other centres promoting such a strategy such as the Interfaith Mediation Centre in Nigeria and the Center for Security Studies in Switzerland. Against such a backdrop, this essay aims to explore the possibility and depth of mediating on religion both in personal matters on a domestic level and in larger political conflicts on an international level.

Part I: Mediation and Religion in the Indian Context

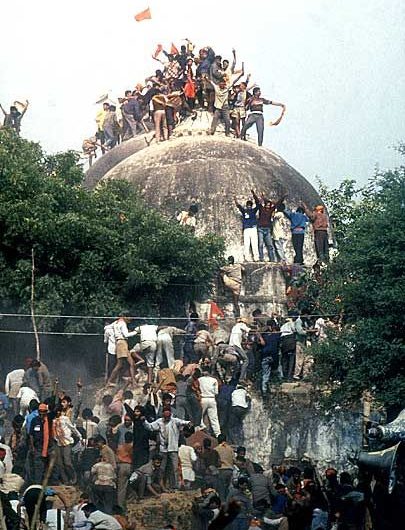

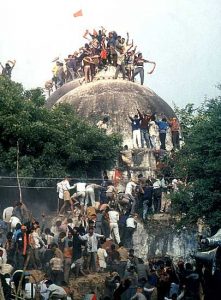

In India, mediation in religious disputes was brought to the forefront by the recent court-ordered mediation in the contested Babri Masjid dispute.[7] Several issues were highlighted during this period such as the credibility of a mediator, being able to address the questions of fundamental rights and equality out of the court, and the possibility of reaching a solution that is not simply acceptable to all parties but is actually just.

Methods of Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR), including mediation, were brought to the Indian judicial system with the introduction of Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) in 2002. The Section empowers civil courts to refer certain matters for out of court settlement under arbitration, conciliation, and judicial settlement including Lok Adalat and mediation. Rule 1A, 1B, and 1C of Order X, CPC are also relevant to judge the procedure laid down for ADR mechanisms in India. Apart from this, the Civil Procedure Alternative Dispute Resolution (SPADR) Rules, 2003 and the Mediation Rules, 2003 contain various guidelines for High Courts to follow when facilitating mediation. Another legislation that covers mediation is the Commercial Courts Act 2015, whereby it is mandatory for parties to exhaust the remedy of pre-institution mediation under the Act before instituting a suit. The Commercial Courts (Pre-Institution Mediation and Settlement) Rules 2018 (the PIMS Rules) have been framed by the government under this Act.

Court referred Mediation is not the only avenue available to Indian litigants. Parties can also go for Private Mediation on their own. While recently, there has been a rise in institutions and organizations helping in such mediation, informal settlements amongst parties to resolve disputes efficiently have often resulted into binding contracts long before since Mediation as a term was recognised in the Indian jurisprudence.

The Law and Jurisprudence: Legislating on Religion and the possibility of Mediation

- The Indian Constitution

India recognises religious rights both for the individual (Article 25, 27 and 28) and the collective (Article 26). However, what is meant by ‘religion’ in a legal context is not explicitly defined anywhere. The Preamble of the Indian Constitution declares India as a secular state – a ‘secularism’ that is defined by an ‘equal respect’ for all religions rather than constructing a ‘wall of separation’ between the State and religion.[8] Aspects of religion are strewn across the Constitution and our substantive law such as in the abolition of untouchability (Article 17), prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion in imposing compulsory service on citizens (Article 23(2)), etc.[9] Schedule VII read with Article 26 of the Constitution also gives various religious matters which can be legislated upon by the appropriate Legislature.[10]

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar during the Constituent Assembly debates stressed on the enormity of the concept of religion and how it permeates into all aspects of the everyday life. He urged the Parliament to strive to limit the definition of religion to beliefs and ceremonies which were essentially religious.[11] In line with this view, the Supreme Court of India has not strictly defined the scope of what constitutes ‘religion’ but rather formulated an ‘essential practices doctrine,’[12] to define the essentialities of religion and reform those practices which are inessential. Judicial precedents, however, have tried to limit the parameters of religion somewhat. In Shirur Mutt,[13] Justice Mukherjee opined that religion was a matter of faith, and not necessarily theistic. In Ratilal,[14] and Durgah Committee,[15] it was emphasized that religion constitutes not merely opinions and beliefs but also outward expressions and acts. In S.P. Mittal,[16] it was held that religion concerns the conscience or the spirit of the man. It is not capable of a strict definition but should be capable of expression in word and deed, such as worship or ritual. Similarly, the expression ‘matters of religion’ under Article 26 extends to acts done in pursuance of religion and covers rituals, observances, ceremonies and modes of worship.[17]

From the plethora of cases brought before the Judiciary to test their constitutionality while simultaneously protecting religious beliefs, it can be gleaned that the Court is not into the business of defining the connotations of what constitutes religion, i.e., regulating people’s beliefs. While there is a presence of a system of rituals over a long period of time, ideas are accepted as religion. It does not matter what their surrounding political or economic considerations might be. The practice adopted by the Judiciary in such cases is to then protect only those practices which can be termed essential based on scriptures and such other sacred text. The Judiciary aims to being in social reform and do away with patriarchal notions.[18] Such cases affect the general public and not just the individuals who file a case.

- The Prevention of Atrocities Act, 1989

Apart from the Constitution, there are several legislations that attempt to adjudicate and punish offences with religious overtones. To meet the demands of Article 17, the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955[19] and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 have also been enacted. Section 3 of the Atrocities Act provides for punishment of offences committed under the Act. It has been held that there is no express provision to compound an offence punishable under the Atrocities Act. However, under special circumstances, the Court can exercise its extraordinary powers under Section 482 of the Criminal Procedure Code to recognize settlement out of court and quash criminal proceedings.[20] But, such a remedy is not available after the High Court has passed its order and a subsequent settlement cannot be reason to bar appeal.[21] Moreover, recently the Delhi High Court laid down stricter guidelines for reference of criminal cases to mediation proceedings and established that the power under Section 482 was not absolute. In cases of grievous charge, even reaching a settlement cannot be reason enough to quash proceedings since doing so would amount to denial of justice.[22] The test is whether the crime is of a personal nature or an offence against the society.[23]

- The Indian Penal Code

Under the Indian Penal Code, Chapter XV relates to offences relating to religion. Section 298 which makes uttering of words with the deliberate intent to hurt religious feelings an offence, is compoundable by the person whose feelings were intended to be wounded. All other Sections under the Chapter (from Section 295 to Section 297) are non-compoundable since they treat the crime as an offence against a class rather than an individual.

- Family laws

The Supreme Court has confirmed that marriage, inheritance, divorce, conversion are as much religious in nature and content as any other belief or faith.[24] Several States in India have enacted Anti-conversion or ‘Freedom of Religion’ Acts which treat forced conversions as non-bailable, cognizable offences. These do not provide for a possibility of using mediation or other ADR methods. Marriage, inheritance and divorce are governed by personal laws of the individuals involved. The Family Courts Act, 1987 is based on the philosophy of promoting conciliation between parties. Section 9 of this Act directs the Family Court to endeavour to resolved family disputes amicably through settlement but do not make such conciliation/ mediation mandatory. Section 23(2) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 also similarly strives for reconciliation between parties. In the landmark case of Afcons Infrastructure,[25] the scope of Section 89 of the CPC was discussed. It was held that family disputes involving marriage, property etc. were suitable for ADR and must be referred to a suitable institution by the Court. The Supreme Court has in fact considered it a duty to encourage settlements of matrimonial disputes, even if the allegations involved are otherwise non-compoundable under the law.[26]

- The Representation of People Act, 1951

Article 225 of the Constitution as well as the Representation of the People Act 1951, put an embargo on incorporating religious considerations in elections. However, such offences impact the public and cannot be treated as simple private disputes. In Afcons,[27] disputes relating to election to public offices were considered generally unsuitable for ADR processes including mediation. When such offences occur, exceptions can hardly be carved out to allow for mediation, since disputes involve technical questions of whether a particular act amounts to an appeal to a particular religion or is simply a candidate making known their devoutness.[28] There is no scope for any mutual agreement.

- Mediation and Religion in India: Arising issues and scope in constitutional matters

The law on mediation is still very limited in scope in India. Apart from the introduction of Section 89 in the Civil Procedure Code and certain legislations incorporating for referral of disputes to mediation,[29] there is no separate law governing mediation in the country. Currently, it is governed under the Legal Services Authority Act.[30] It is non-adjudicatory and the case does not go out of the stream of the control and jurisdiction of the Court even while the matter is before the mediator.[31] Mediation proceedings have been held to be confidential even though this is not specifically provided for under any statute.[32] This makes it difficult for high-profile cases to be referred to mediation since they cannot possibly act as precedent with such confidentiality constraints. The very things that make the process an excellent choice for personal matters, makes it counterproductive for a case involving high stakes and communal emotions.

Religion does not follow logic or reason.[33] It has its own set of rules which may at times appeal to a higher morality but also condones practices which may be otherwise harmful to certain classes of people like women, or the differently abled. It has been settled that simply because an ADR mechanism is established under the personal laws of a religion, it cannot be given legal status or allowed to uphold decisions which infringe upon the rights of a person.[34] Further, claims brought under the Constitution, especially those governing fundamental rights are class action litigations. They affect the rights of classes rather than a simple litigant. In Afcons,[35] representative suits were considered unsuitable for ADR processes since they affect the rights of many and act as res judicata for all similarly affected parties. The private nature of mediation proceedings renders them unsuitable for such cases. In the initial M. Sidiq[36] order, the Supreme Court refused to go into whether the case was representative in nature but the final judgment[37] correctly held that the case affected both Hindus and Muslims as a class and was not limited to the persons joined in the case.

Even though the Mediation Rules provide for qualifications and disqualifications for the appointment of mediators but they are non-binding in nature.[38] In practice, anyone can be a mediator, not necessarily a person with a legal background. Even the ‘expert’ or ‘professional’ mentioned under the Rules, is not defined and can be a broad qualification. For instance, in the Ayodhya mediation, Sri Sri Ravishankar, a spiritual guru, was on the panel of mediators. His presence raised questions of bias since he was openly favourable to one religion, the Hindus, and had no legal background or appreciation for law. In fact, he had himself been in trouble with the National Green Tribunal back in 2017 over the damage caused to the environment by a cultural festival he organized. He had refused to take responsibility for his actions but proceeded to publicly blame the government for allowing his event to occur in the first place. Both his morals and his motivations on the panel were suspect. The background and qualifications of mediators is of crucial concern in a religious mediation due to the sensitivity of the subject matter. The mediator needs to be knowledgeable of different dogma, respectful of the sentiments of diverse parties, and have a sound understanding of the law as well. In an inter-religious dispute, the religion professed by the mediator himself can be a possible conflict of interest.

Lastly, there is hardly ever a purely religious controversy. The Babri Masjid dispute, the Sabarimala case, the triple talaq case, all have political considerations intertwined within the disputes. This makes it difficult to define a ‘religious dispute’ suitable for mediation in the first place, i.e. does the role played by political parties render the dispute unsuitable fore mediation since elected officials are accountable to all citizens and any dispute involving them cannot be personal, or whether it is possible to separate their role from a purely “religious” question, as was unsuccessfully attempted in the Ayodhya mediation, even the genesis of the dispute can traced back to vote bank politics? It also allows for the spotlight to be taken away from the crux of the problem which might be staged and institutional and rewrite it as merely a personal matter airing individual concerns. This can help trivialise an issue instead of setting a justiciable precedent.

Part II: Mediation and Religion in other Countries and International Politics

Mediation can be done for larger religious conflicts. Under such a mediation, the mediator can ideally be any neutral party, irrespective of whether he has any religious affiliations himself. This is part of religious dispute-based mediation. There is also a concept of faith-based mediation, where people with knowledge of religion, act as mediators based on the spiritual order from god regardless of the presence of a ‘religious’ dispute.[39] This form of mediation uses the innate ideals which are common to all religions, such as love, unity and harmony, to create a dialogue of peace-keeping. The role taken by such mediators who may also be religious leaders with considerable clout with the people is crucial in a political conflict since their presence reflects a deeper sense of legitimacy and their message is considered devoid of personal greed.[40]

Historical and theological basis to faith-based mediation

- Mediation of disputes as per Christianity

Mediation in Christianity is promoted in the Bible. This is elucidated in several verses in the Bible which talk about “promoting reconciliation and forgiveness for everyone allowed.”[41] Other passages in the Bible also talk about not taking a fight to court but solving it amongst on a personal level to maintain the relationship. It also takes into account mediation as a method to resolve disputes between two individuals who are not Christians, to help maintain relations and harmony.[42] This does not only extend to religious disputes but talks about all possible kinds of disputes. There is also talk about having ministries of people, rather than courts, to mediate disputes.[43] These ministries of people are to be formed from amongst the clergy. Thus, Christianity promotes faith-based mediation.

- Mediation in Islam

Similar to Christianity, Islam also promotes mediation. It gives the mediator the highest respect possible and talks about a committee along the same lines as the Christian Ministry of Justice. There is no bar on the kind of disputes that can be mediated and mediation is also permitted with people of other communities, to maintain peace and harmony.[44] Every Religious text including the Quran, Sunna, Ijma and Qiyas, talks about mediation of disputes. Thus, Islam also promotes faith-based mediation.

- Mediation in Hinduism

Under Hinduism, mediation in religious disputes dates back to the time of Mahabharata when Lord Krishna, unsuccessfully tried to mediate between the Kauravas and Pandavas to stop the battle of Kurukshetra.[45] This episode of the Mahabharata brought out the prioritization of maintaining relations, over fighting in a war and also promoted a reconciliatory method of dispute resolution. As per certain scholars, Hinduism also had mediation in the Vedic times, where Agni or the fire god acted as a mediator between humans and the supernatural. This was called the Vedic Mediation.[46] That later translated to Brahmanical Mediation, where the Brahmins or the priestly class played a role of the mediator between god and the common people to resolve disputes.[47] As often the order of Brahmins, was perceived as an order of God, which was seen as the ultimate dispute solver. Thus, it can be said that Hinduism promotes faith based mediation.

Therefore, it can be said that faith based mediation is the most popular method to solve religious disputes. Religious leaders are revered, and their decisions considered gospel. But over the years, faith-based mediation witnessed a decline in favour of more rigid procedure since such unregulated mediation often led to arbitrary decisions, which were often to maintain the teachings of the religion, even if they were unjust.

Mediating religious disputes in other countries

As discussed above, religion talks about maintaining relationship and harmony, this has also been incorporated into practice by several countries.

- Italy

Most of the European Union has common laws on mediation. The prevalence of Christianity has led to the recognition of Papal mediation, a faith-based mediation by the Pope. Italy is located near the holy land of Vatican City, the seat of Christianity. The first recorded case of religious mediation in Italy dates back to 1226. It was between the Roman Empire and Lombard League.[48] It was a Papal mediation, to resolve the dispute between the parties, who agreed to the said outcome, due to the sheer respect, they had for the pope. However, Papal mediation, slowly faded out in Italy, since it was costly and decisions became arbitrary as the Pope was the only figure of authority.[49] Mediation happens as per the guidelines of European Union, where separate religious tribunals exist for faith based mediation.[50] Therefore, religious disputes may be mediated, if the parties wish so, else they are taken up by the court.

This is different to the situation of Vatican City, where Papal Mediation is still practiced. This is because the Pope is a figure of authority who is regarded the ultimate connection between god and mankind.[51]

- USA

The population of USA practices three major religions namely Christianity, Judaism and Islam.[52] Any religious dispute is often dealt with by mediation, as per religious laws.[53] However, the US courts have always followed the principle of maintaining a wall of separation, between church and state.[54] This wall exists due to the first amendment. This amendment prohibited the government to make any laws propagating a particular religion.

Throughout history, US courts have refused any intervention in religious disputes, this has led to the establishing of religious tribunals to mediate religious disputes. The decisions of these organizations, have been given the same weightage as court decisions.[55] For instance, the catholic mediation organization has been created to take care of religion disputes amongst Catholics.[56] Similarly, other religions are given full autonomy to solve religious disputes amongst them.[57]

- Nigeria

Prior to colonization, Nigeria adopted a system of mediation to resolve all kind of disputes, this was way before it was colonized.[58] After colonization, the court system was introduced in Nigeria. However, it still adopts a mediation-based procedure for most of its civil disputes, depending on the religion of the party.

The respected religious elder of the parties that have a dispute, often act as mediators to bring about a resolution, before the formal system of courts comes in.[59] Similar to the US, there are separate organizations, an example being the Christian Association of Nigeria, that exist to handle all form of religious mediation.[60]

Apart from intra country based disputes, faith based mediation also plays a role in inter country, religious politics.

- Mediation and Religion in International Politics

Over 80% of the world’s population identifies with a religion. Religion influences many aspects of a person’s personal, social and political lives. It is thus not surprising that religion also plays a role in conflicts, and that religious conflicts have been on the rise. In 1975, the proportion of armed conflicts with a religious motivation for at least one of the parties involved was around 1/3. In 2015, this was the case for 56% (or 2/3) of all armed conflicts around the world.[61] Research suggests that such conflicts are harder to control and less likely to be solved through existing conflict resolution mechanisms.[62] This is largely due to a gap in communication and unflinching positions taken by warring sides.

Faith-based mediation has not been completely absent in the modern age.[63] Major international political conflicts involve several talks between leaders behind the stage, which while may be informal, are also at times formalised and mediated upon by a neutral party. There is a call for such mediators to recognise the multi-faceted nature of a religious conflict and employ a model which takes into account the beliefs of people as well as acknowledges religion as a permeating institution unto itself.

The Iraqi Inter-Religious Congress of 2007 (IIRC) was one such example of a mediated settlement which was both religious and involved different state actors. The Iraqi society had a history of religious tensions amongst faction groups, particularly the Shia and Sunni Muslims, which was exacerbated by the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Between 2003 and 2006, Iraq faced major political upheaval, and its administration almost came to a standstill. During this period of turmoil, religious leaders stepped in to provide wary citizens with civil, medical and social services.[64] Canon Andrew White, a clergyman and pastor ran an organization called the Foundation for Relief and Reconciliation in the Middle East (FRRME) and was instrumental in getting religious and tribal representatives from the Muslim factions in the country as well as from other minorities such as the Christians, together in dialogue with the US and Iraq authorities as the first Iraqi IIRC in June 2007.[65] The Congress resulted in the Iraqi Inter-Religious Accords which denounced violence and called for national unity. While this was not an end-all solution to the conflict, it was the beginning of a dialogue and a start of adopting a more non-violent approach in a situation which was only worsening over the years. The FRRME addressed not only the socio-economic plight of the nation but also the faith-based ideals of the religious leaders. They focused on common theological principles of a deep-seated humanity and ultimate accountability to God rather than on sectarian hatred.

The Inter-Religious Council of Sierra Leone (IRCSL) was also a similar example. The country saw a brutal civil war which started in 1991 and raged on until 2002. In the middle of the war, in April 1997, religious leaders from the Muslim and Christian communities came together to establish the IRCSL and advocated for a peaceful negotiated settlement to the conflict. The IRCSL was instrumental in persuading the then president of Serra Leone and the leader of the rebel group Revolutionary United Front (RUF) to enter into a negotiation. During the negotiations, the IRCSL participated as informal mediators and kept the dialogue going whenever it seemed that the parties had reached an impasse.[66]

Imam Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye, who were leaders of competing militias in Nigeria, were able to reconcile and form the Interfaith Mediation Centre, which trains former militia members to become peace activists. Their extraordinary story, which has been the subject of two celebrated documentaries[67] started as an informal mediation of sorts by a close friend who brought them together to talk and helped them realise their similarities.[68] They initiated important conflict transformation work in Nigeria and even proceeded to successfully mediate an ethnic conflict in Kenya. But a settlement by mediation does not ensure a lasting resolution in all cases. Libya is a country which has been facing Islamic extremism, political unrest and civil war since 2011. In 2015, a UN-led mediation in Libya steered the brokering of a power-sharing agreement, the Libyan Political Agreement, between rival parliaments. However, the mediation reflected only on the political strife, and it did not address the religious ideals (though extreme) of the Islamist parties. The Agreement was signed hastily and lacked both inclusivity and legitimacy, the signees signed it in an individual rather than a representative capacity. It also suffered from other problems such as the setting of an unrealistic deadline, lack of support from the UN Security Council, the UN portraying instances of partiality, and continually changing positions of the international community. The UN mediation in Libya has thus suffered from a lack of vision which failed to close the divide between regional and international actors.[69]

- The Pros and Cons of faith-based mediation

Faith-based mediation, particularly those involving regarded religious leaders, gives the process a higher sense of credibility and ensures that parties can look past their differences and engage in a dialogue for collective betterment. It can lead to quicker resolutions due to the absence of complex procedural rules as well discretion on the parties to decide the outcome of their dispute by mutual deliberation and agreement. The same reason can also lead to a longer process when the parties are unwilling to look past their differences since there is no mandate to compulsorily reach a solution. The role of the mediator is thus very important to ensure that discussions do not get heated and that a constant dialogue is maintained. The mediator should be able to remain value neutral and set aside his own biases when faced with such a conflict. The mediator needs to be trained in the art of diffusing high-tension situations and be well versed in the nuances of the dispute.[70] A narrow approach, ignoring the multi-faceted complexities of the conflict can lead to an ineffective solution as seen in the case of Libya.

Simultaneously, it is important to recognise mediation as an alternate resolution mechanism to create a dialogue where none exists. Too much power should not be given to representatives of communities or mediators when the conflict involves grave crimes done against humanity which need to be punished by the law. While dealing with a religious dispute, which is communal and not personal such as family law matters, there are people affected by the result of the mediation who cannot be privy to the proceedings. There is a possibility of their experiences and grievances being discounted and them being forced to accept solutions which ignore their personal plight. There may be times when reaching a resolution is dependent on the instigators not being held accountable for the crimes perpetuated by them. In such a situation, the third parties need to be mindful of the dilemmas and trade-offs they are likely to face while mediating violent conflicts.[71]

Conclusion

It is crucial to weigh in the pros and cons of mediating a religious dispute before engaging in such a tactic. This is especially necessary when the dispute involved is high stakes and holds the fate of large communities in its hands. A poorly handled mediation in such a scenario can worsen the situation to a point of no return. It is imperative for the mediator to be mindful of the emotionally charged situation on both ends whenever closely held beliefs are questioned on the negotiating table. What is required is the ability to separate doctrine from interpretation and be careful about being impartial and seemingly favouring any side or interpretation. The conversation can be brought back to God, any God, being the ultimate judge and jury of one’s actions to initiate peacebuilding exercises where a deadlock might have reached otherwise. At the same time, it is important to not lose track of the complexities of the dispute and place too great an emphasis on the decisions taken by a few representatives in private. Mediation should be used to initiate dialogue and bring about resolution of conflict, not used as a method to deny justice to masses who might have been affected by the prior actions of political leaders or communal politics.

[1] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, 10

December 1948.

[2] Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Art. II, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, 9 December 1948 (The Article protects religious minorities from threat under the Genocide Convention).

[3] Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Art. I(a)(2), Resolution 2198 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, 28 July 1951 (The Article includes within the definition of a ‘refugee’ a person who is facing persecution because of their religion).

[4] Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, 14 November 1970.

[5] The Case Concerning the Rights of Minorities in Upper Silesia (1928); the advisory opinion (AO) concerning Greco-Bulgarian Communities (1930); AO concerning Minority Schools in Albania (1935).

[6] The International Court of justice was posed with such a decision in the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2004 ICJ 136. It proceeded to link the right to access holy sites to the right to movement under the ICCPR, rather than able to find a way to foster dialogue and further conflict resolution.

[7] M. Siddiq (D) v. Mahant Suresh Das, Civil Appeal No. 10866-10867 of 2010, order dated 8 March 2019.

[8] S.R. Bommai vs. Union of India, (1994) 3 SCC 1.

[9] Some other provisions under the Constitution are Article 48, Article 290A, Articles 331 – 366, Article 370A, Article 370G.

[10] For instance, family law matters, charitable institution and religious endowments are given in the concurrent list, pilgrimage within India is given in the State list, while pilgrimage outside India is given the Union list.

[11] Constituent Assembly Debates VII: 781.

[12] The Doctrine was first formulated in Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras vs. Sri Lakshimindra Thirtha Swamiar of Sri Shirur Mutt, AIR 1954 SC 282.

[13] Id.

[14] Ratilal Panachand Gandhi v. State of Bombay, AIR 1954 SC 388.

[15] Durgah Committee Ajmer vs. Syed Hussain Ali Brothers, (1962) 1 SCR 383.

[16] SP Mittal v Union of India, AIR 1983 SC 1.

[17] Jagannath Ramanuj Das vs. State of Orissa, AIR 1954 SC 400.

[18] Indian Young Lawyers Association vs The State of Kerala

[19] Earlier called the Untouchability (Offences) Act.

[20] Dhananjay Gopalrao Bahergaonkar and Ors.vs. The State of Maharashtra, in the High Court of Bombay (Aurangabad Bench) Criminal Application No. 2505 of 2010, Decided On: 16.08.2010; Deep Sharma and Ors. vs. State of Uttarakhand and Ors. in the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital Compounding Application No. 402 of 2019 in Criminal Miscellaneous Application No. 314 of 2019, Decided On: 01.03.2019; Aaley Mohd. Iqbal and Ors.Vs. State NCT of Delhi and Ors., in the High Court of Delhi Crl. M.C. No. 4053/2015 Decided On: 30.09.2015; Satish and Ors.Vs. State of Maharashtra and Ors., in the High Court of Bombay (Aurangabad Bench) Criminal Application No. 5425 of 2014 Decided On: 08.01.2015.

[21] P. Ramaswamy vs. State (U.T.) of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, (2013) 14 SCC 57.

[22] Sh. Yashpal Chaudhrani & Ors. vs State (Govt. Of NCT Delhi), in the High Court of Delhi, Crl.M.C. 5768/2018, Decided on April 22, 2019.

[23] Gian Singh vs State of Punjab, (2016) 184 PLR2 93. Affirmed in Dimpey Gujral Vs. Union Territory through Administrator U.T. Chandigarh and Others, AIR 2013 SC 518; Parbatbhai Aahir Vs. State (2017) 9 SCC 641

[24] Sarla Mudgal vs. Union of India, (1995) 3 SCC 635.

[25] Afcons Infrastructure v Cherian Varkey Construction Co. P Ltd and Others (2010) 5 AWC 5409 (SC).

[26] Jitendra Raghuvanshi and Ors. Vs. Babita Raghuvanshi and Anr., (2013) 4 SCC 58; K. Srinivas Rao vs. D.A. Deepa, Special Leave Petition (Civil) No. 4782 of 2007.

[27] Supra note 25.

[28] See Jagdeo Sidhanti vs. Pratap Singh, AIR 1965SC 183; Shubh Nath vs. Ram Narain, AIR 1960 SC 148; Damodar Tatyaba vs. Vamanroa Mahadik, AIR 1991 Bom 373.

[29] See Section 442 of the Companies Act, 2013, read with the Companies (Mediation and Conciliation) Rules, 2016; The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) Development Act, 2006; Section 32(g) of the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 etc.

[30] Supra note 25.

[31] Id.

[32] Moti Ram (D) Tr. LRs and Anr. Vs. Ashok Kumar and Anr., Civil Appeal No 1095 of 2008 dated 17.2.2010.

[33] Supra note 24.

[34] Vishwa Lochan Madan vs. Union of India, (2014) 7 SCC 707.

[35] Supra note 25.

[36] Supra note 1.

[37] M. Siddiq (D) v. Mahant Suresh Das, Civil Appeal No. 10866-10867 of 2010, order dated 9 November 2019.

[38] Rule 4 provides for retired judges, legal practitioners, experts or institutional centres to be mediators. Rule 5 excludes people who have been declared insolvent, are facing criminal charges, etc.

[39] Ricardo Padilla, Understanding faith based mediation: A multidimensional model, Mediate https://www.mediate.com/pdf/UnderstandingFaithBasedMediationPadilla.pdf.

[40] Jacob Bercovitch & Ayse Kadayifci, Religion and Mediation: The role of faith based actors in international conflict resolution, 14 International Negotiation, 175, 177 (2009).

[41] David Masci & Elizabeth Lawton, Applying God’s law: Religious courts and mediation in US, Pewforum, http://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/08/applying-gods-law-religious-courts-and- mediation-in-the-us/.

[42] Louisiana State Bar Association, Mediation and Religion: General Attitude of Three Major Religion in United States, Louisana Bar Association, https://www.law.lsu.edu/experiential/files/2018/01/Mediation-and-Religion.pdf.

[43] Id.

[44] Abdul Azeez Sirajudeen, Concept of Mediation in Islamic Jurisprudence, Abdul Azeez Sirajudeen, https://www.academia.edu/3048074/Mediation_in_Islamic_Jurisprudence.

[45] Matthew R. Sayers, Claiming Modes of Mediation in Ancient Hindu and Buddhist Ancestor Worship, 26 Journal of Ritual Studies, 5 (2018).

[46] Id.

[47] Sayers, supra note 45.

[48] F Matthews Giba, Religious Dimensions of Mediation, 27 Fordham Urban Law Journal, 1695, (2000).

[49] Id.

[50] Giorgio Fabio Colombo, Alternative Dispute Resolution in Italy: European Inspiration and National Problems, RLR (Nov. 29, 2012), http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/cg/law/lex/rlr29/Colombo.pdf.

[51] Emma Altheide, Vatican Mediation and Venezulean Crisis, 1 Missouri Law, 249, 257 (2018).

[52] Louisiana State Bar Association , supra note 42.

[53] Id.

[54]John S. Baker Jr, Other Articles in Legal Terms and Concepts Related to Religion, MTSU, https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/886/wall-of-separation.

[55] Michael C Grossman, Is this Arbitration?: Religious Tribunals, Judicial Review, and Due Process 107, Columbia Law Review 169, 172 (2007).

[56] Id.

[57] Id.

[58] Olufemi Abifarin et al, Dispute Resolution within/between Religious Organization in Nigeria: Litigation or ADR?, Gambia Law, http://gambialawreview.gm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=30:1-dispute-resolution-within-between-religious-organisations-in-nigeria-litigation-or-alternative-dispute.

[59]Id.

[60] Abifarin, supra note 58.

[61] Jonas Baumann et al, Rethinking Mediation: Resolving Religious Conflicts, Center for Security Studies (2018).

[62] Id.

[63] Owen Frazer and Richard Friedli, Approaching Religion in Conflict Transformation: Concepts, Cases and Practical Implications, Center for Security Studies.

[64] Michael A. Hoyt, The Religious Initiative for National Reconciliation in Iraq, 2006-07, in, The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Security (Chris Seiple et al, 2013).

[65] S.K. Moore, Military Chaplains as Agents of Peace: Religious Leader Engagement in Conflict and Post-Conflict Environments, 189 (2013).

[66] Thomas Mark Turay, Civil society and peacebuilding: The role of the Inter- Religious Council of Sierra Leone, in, Paying the Price: The Sierra Leone Peace Process (David Lord, 2000).

[67] The Imam and the Pastor, and An African Answer

[68] See A Discussion with Pastor James Wuye and Imam Muhammad Ashafa, Berkley Centre (2009) https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/interviews/a-discussion-with-pastor-james-wuye-and-imam-muhammad-ashafa.

[69] Lisa Watanabe, UN Mediation in Libya: Peace Still a Distant Prospect, CSS Analyses in Security Policy (Jun. 2019).

[70] See Angela Ullmann, Training on Religion and Secularity in Conflict for Peacebuilding, Center for Security Studies (2017).

[71] See Anne Isabel Kraus et al, Dilemmas and Trade-Offs in Peacemaking: A framework for Navigating Difficult Decisions, 7 Politics and Governance 331, (2019).